Loren Bonner

The initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has worn off. Fast forward 3 years later to today, and a clearer picture has emerged of both the individual as well as broader organizational effects of prolonged stress from the pandemic. Some pharmacy personnel are leaving, others are experiencing apathy, and there are clear threats to patient safety.

“What we have learned collectively is that everybody is at risk of experiencing burnout and organizations need to pay attention to sustained chronic stress,” said Nancy Alvarez, PharmD, FAPhA, from the University of Arizona R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy. “We can manage and address emerging situations—emergency situations—for short periods of time, but we can’t do this for sustained periods of time.”

While workplace issues and the need to improve pharmacy staff’s well-being are not new problems, the pandemic put a public spotlight on them.

“These problems and burnout are a big problem across many practice settings, yet lived experiences of pharmacy personnel do not seem to be characterized solely by burnout.” said Alvarez. “It appears that there is a gap in our understanding of how moral distress and moral injury apply to pharmacy personnel similar to what has been described for veterans who return from war.”

As all health care personnel across the board are facing these challenges right now, organizations representing them are all trying to find solutions to well-being—for the short term and the long term.

The problem

Workplace conditions continue to be the primary reason cited for prolonged stress and burnout in the nearly 1,300 reports submitted to the Pharmacy Workplace and Well-being Reporting (PWWR) portal since it launched in October 2021. The portal, developed jointly by APhA and the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations (NASPA), is a confidential and anonymous way pharmacy personnel can report positive and negative experiences in pharmacy practice as well as suggest solutions. Comments are collected and analyzed by a patient safety organization to afford legal confidentiality protections.

Many organizations recognize that systems issues within a workplace are a major cause for burnout among health care professionals, and call for the focus to be on correcting them. In their National Plan for Health Workforce Well-being, for example, the National Academy of Medicine singles out

government, payers, industry, educators, health care leaders, public health leaders, and those in other sectors to help drive policy and systems change.

In the PWWR reports, pharmacy personnel have said that employers may have well-being resources on hand, but workplace issues are still not being addressed.

“I think that many of the issues are systemic and do not enable rank-and-file people to care for the issues,”

said Alvarez, who was chair of the APhA/NASPA workgroup whose work included PWWR, a state-based national survey, and the Pharmacists’ Fundamental Responsibilities and Rights document.

Other key findings that have emerged as the PWWR reports have been analyzed quarterly, include

Harassment by patients, coworkers, and pharmacy and nonpharmacy managers is a real problem.

Two-way lines of communication are not perceived to be open.

Positive experiences have a long-term positive effect on well-being.

Even in the context of workplace and systems issues needing to be addressed by organizations in the long term, Alvarez asks, “What small things can an individual do today?”

Short-term solutions

Pharmacists report “unimaginable” stress from interruptions, aggressive patients, increased workload, and staffing issues. It’s a concern across practice settings and in all roles of pharmacy.

Cynthia Knapp Dlugosz, BSPharm, NBC-HWC, a certified mindfulness teacher and one of the first national board-certified health and wellness coaches in the United States, said there are ways pharmacists can manage stress and anxiety in the moment while at work.

“Stress and anxiety are tied to our prehistoric threat defense system,” said Knapp Dlugosz.

“Our fight-or-flight reaction gets triggered, and our thoughts keep us stuck there.”

At APhA2023 in Phoenix this year, Knapp Dlugosz led a session—"Right Here, Right Now: Managing Stress and Anxiety in the Moment"—in which she shared evidence-based techniques for shifting from sympathetic to parasympathetic activity, to respond to stress and anxiety more productively.

Here are the 5 steps she recommends pharmacy staff can take:

1. Reclaim your attention. The most important first step is to return your focus to the present moment.

2. Breathe for calm. Breathe from your diaphragm rather than chest and make the exhalations twice as long as inhalations (e.g., breathe in for a count of 2 and out to a count of 4).

3. Notice you are all right. As you inhale and exhale, say to yourself “Right now, I am all right”—because in that moment, you probably are.

4. Shake it out. Dissipate the fight-or-flight energy by shaking your body for a few seconds or tensing up all of your muscles tightly and then releasing them.

5. Reset thoughts. In a calmer state, you can examine the thoughts that are fueling stress and anxiety. You have to start appreciating your thoughts as mental events and not facts. Ask yourself: how are my thoughts making the situation worse?

Some pharmacy settings have attempted to correct workplace issues that are causing stress.

Lam Nguyen, PharmD, from Oregon Health & Science University Hospital, said that his pharmacy department worked with the hospital’s human resources department to develop new concepts for workload. They designed a workweek with 4 full-time equivalents (FTEs) that were needed rather than four 1.0 FTEs. “We actually realized ‘why not create five 0.8s?’ This allowed our staff to have more balance in [their] workload, and it’s been well-received,” said Nguyen, who spoke on an APhA podcast about burnout.

On the same podcast, Jessica O’Brien, CPhT, a community practice pharmacy supervisor at Mayo Clinic, said she believes staffing issues are the main contributor to burnout among employees across all of health care. In the pharmacy department where she works, they are putting stay interviews into practice with employees, giving them a chance to share what is working well and where there are opportunities to improve. “I feel this helps give [employees] a voice and helps them feel valued as an employee, that we are listening to their concerns,” she said.

Specific to pharmacy technicians, pharmacy leadership within Mayo Clinic has worked to make the pharmacy technician profession more than just a job. They employ a career ladder concept in which pharmacy technicians can choose multiple pathways for their career, such as education or research, and obtain additional training in those chosen areas.

“I really think this is going to change the profession for pharmacy technicians [because] they will be able to grow in their career and it gives more meaning to their work,” O’Brien said. “They can see the big picture and the impact they are having on people.” She believes it will help decrease technician turnover, too.

According to Long Trinh, PharmD, former senior director of pharmacy at Providence in Portland, OR, the financial impact of turnover in hospitals is a top CEO concern today.

His hospital quantified the cost of turnover and estimated that for every one pharmacy technician turnover, it would cost $25,000 to $35,000 per turnover. The average cost of a pharmacist or leader turnover is 4 to 6 times greater than that of a technician.

“For a large health system with a 40-technician turnover per year, this could incur an estimated cost of 1 to 1.4 million dollars annually—so there’s a financial impact,” said Trinh, who also spoke on APhA’s podcast about burnout.

Lemrey “Al” Carter, PharmD, RPh, executive director of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP), believes one of the most recent positive steps forward in improving pharmacy workplace conditions has been giving technicians more authority.

“One of the biggest moves is seeing pharmacy technicians having a much greater voice and seeing boards of pharmacy allow technicians to perform more nonclinical roles,” Carter said.

Long-term solutions

Remedying workforce issues in both community and health-system pharmacy won’t happen overnight.

Trinh said to address burnout, leaders must go back to the fundamental principles of workforce planning and design and look for opportunities to redesign work.

Questions leaders should ask, according to Trinh, are

Do we have enough people to do the work?

Are people adequately trained to do the work they are expected to do?

Are people compensated equitably to the market for the work they are being asked to do?

“By addressing these, I feel, long-term, we will be able to cover and renew and rebuild a sustainable workforce,” said Trinh.

Carter said partnerships are vital going forward in order to achieve any meaningful change.

“Partnerships have to happen because there are so many issues at play here,” said Carter.

For instance, NABP and other pharmacy organizations need to continue working with the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. An NABP workgroup identified schools and colleges of pharmacy as being integral stakeholders in developing a new pharmacy practice model, “as enrollment has significantly decreased while the need for pharmacists has increased,” noted the report the NABP workgroup published in 2022. “If these trends continue, there will not be enough pharmacists to meet the health care needs of communities throughout the country, especially in more rural areas.”

“With working conditions and well-being, it takes a village and we are working with all the pharmacy associations and partners on the state and federal level,” said Carter.

The NABP report cited some specific and achievable solutions as pharmacy partners envision and collaborate on a new pharmacy practice model. They include

Providing pharmacy staff with opportunities to work from home with fewer interruptions to complete nonpatient-facing tasks, including data entry, data verification, and third-party adjudication

Encouraging employers and state boards of pharmacy to support efforts to increase the use of call centers that provide patients the convenience and time to discuss concerns and ask questions while freeing up staff in the community setting for more clinical tasks

Suggesting that central fill operations should be used to relieve busy pharmacies and that the central fill pharmacies should be permitted to mail medications directly to patients rather than having to ship them back to the originating pharmacy

Identifying and setting meaningful standards for lunch breaks, shift lengths, well-being of pharmacy personnel, and practice standards for clinical functions through stakeholder collaborations.

Having a voice

According to WHO, not feeling valued or heard is a hallmark symptom or risk that can lead to burnout.

In the PWWR reports as well as in APhA’s Well-being Index for Pharmacy Personnel, pharmacy staff report over and over that they are not being heard or valued when they’re trying to speak with a supervisor.

According to the latest PWWR findings, two-thirds of those who submitted comments about negative experiences involving lack of open communication channels said they offered recommendations to management, but 83% of those individuals said their recommendations were not considered or applied, causing them to feel ignored and unvalued.

“Just giving [staff] a voice so they feel heard and valued is really going to help in the long run for your whole team,” said O’Brien.

While it’s distressing for pharmacy personnel and the profession to be at this point, Alvarez said it’s an opportunity to name the lived experiences for what’s happening and act in such a way that the profession, including those who have influence to affect systems changes, will have collective resilience.

“We can advance as a profession out of this,” Alvarez said. “Not only pharmacists, but all those involved so that pharmacists and pharmacy personnel are able to safely and effectively help people use medications for optimal health and wellness.” ■

What is moral injury?

Moral injury was first described in service members who returned from the Vietnam War with symptoms resembling PTSD, but who exhibited symptoms beyond that diagnosis and did not respond to standard PTSD treatment.

Research revealed a different driver behind the two, wherein those with PTSD experienced a real threat to their mortality, and those with this different presentation had experienced repeated insults to their morality. They had been forced, in some way, to act contrary to what their beliefs dictated as moral beings.

Moral injury can happen when one perpetuates, bears witness to, or otherwise fails to prevent an act that transgresses deeply held personal moral beliefs. In the health care space, this can include the oath taken as health care providers to put the needs of patients first. ■

PBMs play big role in negative working conditions

Jonathan Little, PharmD

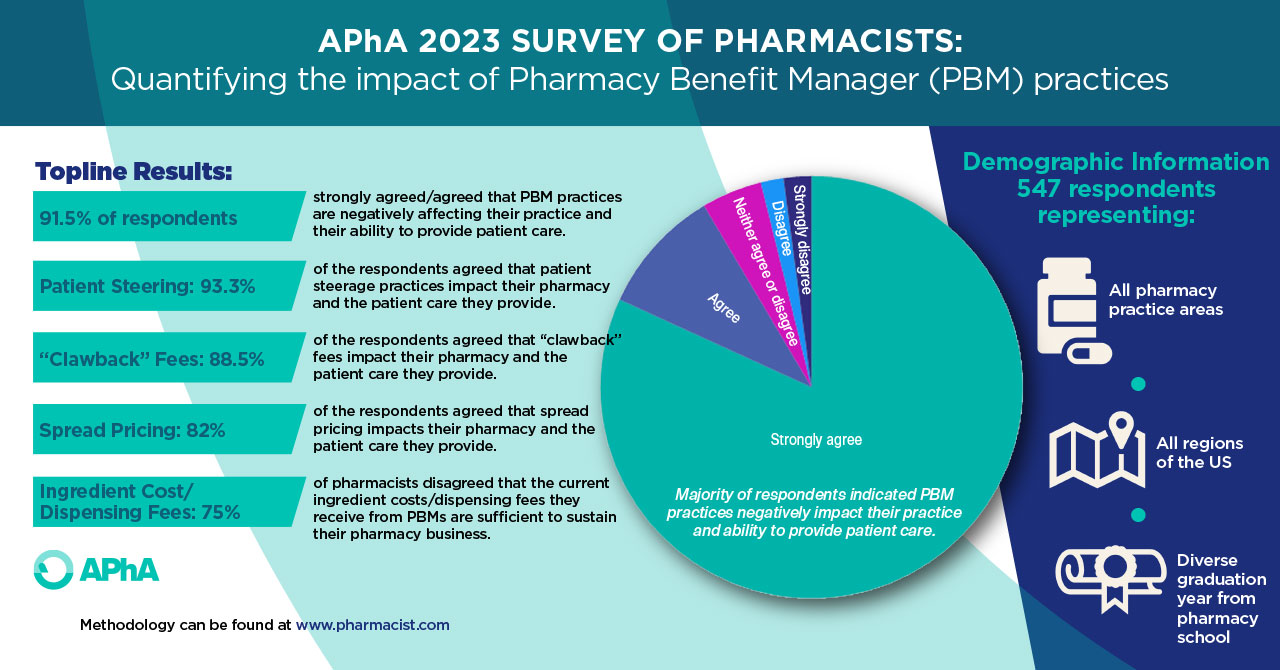

Well-being in pharmacy is affected by workplace conditions, PBM practices, and burnout—all of which may be related.

APhA and the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations’ Pharmacy Workplace and Well-being Reporting (PWWR) tool, an online anonymous service for pharmacy personnel to submit their experiences, conveys several eye-opening findings on the difficulties that pharmacy team members must deal with in their practice settings.

In new findings released by APhA in March 2023, working conditions were the most commonly cited source of negative experiences for pharmacists. This could include anything from prescription workload, vaccination demands, staffing levels, number of hours worked, lack of breaks, and/or other issues.

Many anecdotal stories about poor well-being are supported by the most recent APhA Pharmacy Workplace Survey, in which the authors conclude “pharmacy personnel’s workplace issues and their relationship to personal well-being continue to be a critical, complex issue across all practice settings.”

If pharmacists are unable to provide the exceptional patient care that they are capable of providing, patients lose in the end. This, too, is supported by data, as pharmacists recently described several issues that interfere with their ability to provide patient care in APhA’s survey on PBM practices.

Respondents overwhelmingly described the negative effect that PBM practices have on their ability to provide patient care. While PBMs may not be the only source affecting well-being issues in pharmacy, there is little doubt of the large role they play. This is yet another contributing piece to the problem of impaired well-being in pharmacy.

Recent research conducted by the University of Illinois Chicago found that “nearly 9 in 10 pharmacists were found to be at high-risk for burnout,” and the reasons for this are multifactorial.

Pharmacists are extremely valuable members of the health care team, but the impact that pharmacists can make in patient care is highly related to the pharmacist’s own well-being. Improving these issues—especially workplace conditions, PBM practices, and burnout—in pharmacy will in turn improve pharmacy team members’ well-being, which ultimately will allow for the delivery of high-quality patient care. ■

NABP recommendations

The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) 2022 workgroup report on workplace safety, well-being, and working conditions, recommended that

1. NABP collaborate with stakeholders to

a. Identify new practice models that support pharmacists’ ability to provide patient care services

b. Identify/set meaningful standards for staffing to include but not be limited to

i. Lunch breaks/shift lengths

ii. Well-being

iii. Clinical functions

iv. Use of automation technology

v. Use of pharmacy technicians

2. NABP review the Model Act to identify model act language that can create barriers to care and suggest edits to submit to the Committee on Law Enforcement/Legislation

3. NABP encourage industry stakeholders to amplify current messaging to educate patients about pharmacy operations to manage expectations

4. NABP encourage boards of pharmacy to consider pathways to innovation such as automation and central fill, reimagine new delivery models that support pharmacists’ ability to provide patient care services, and address staffing shortages

5. NABP encourage boards of pharmacy to review and revise regulations to utilize pharmacy technicians to augment the role of the pharmacist and to identify current pharmacist-only duties that could be safely and competently performed by nonpharmacist personnel ■